January | Art & Culture

Fashion’s Secret Rebel Queen

One of fashion’s original rule-breakers, Caroline Baker brought her inspired storytelling and maverick approach to clothing to some of the most thrilling imagery of the last fifty years from NOVA covers to Benetton ads. A new book celebrates the far-reaching influence of this glorious rebel and suggests what we might all learn from her today

Sarah BaileyMake a statement, originate, don’t imitate, make your own i-D,” was Caroline Baker’s rallying cry in the debut issue of the iconic magazine title. The maverick stylist, who has inspired generations of readers to express themselves through what they wear (from her radical, era-defining work at Nova, Cosmopolitan, i-D and beyond), is the subject of a new book Rebel Stylist: Caroline Baker – The Woman Who Invented Street Fashion, by Iain R. Webb, the fashion academic, writer and curator.

In this lovingly researched volume, Webb makes the case that Baker’s iconoclastic sensibility and DIY aesthetic set the blueprint for the role of the creative, collaborative fashion director/image-maker as we understand it today. In fact, it is impossible to imagine the influential careers and impact of, say, Katie Grand or Dazed’s current editor-in-chief, Ib Kamara, without acknowledging the groundwork that Baker laid.

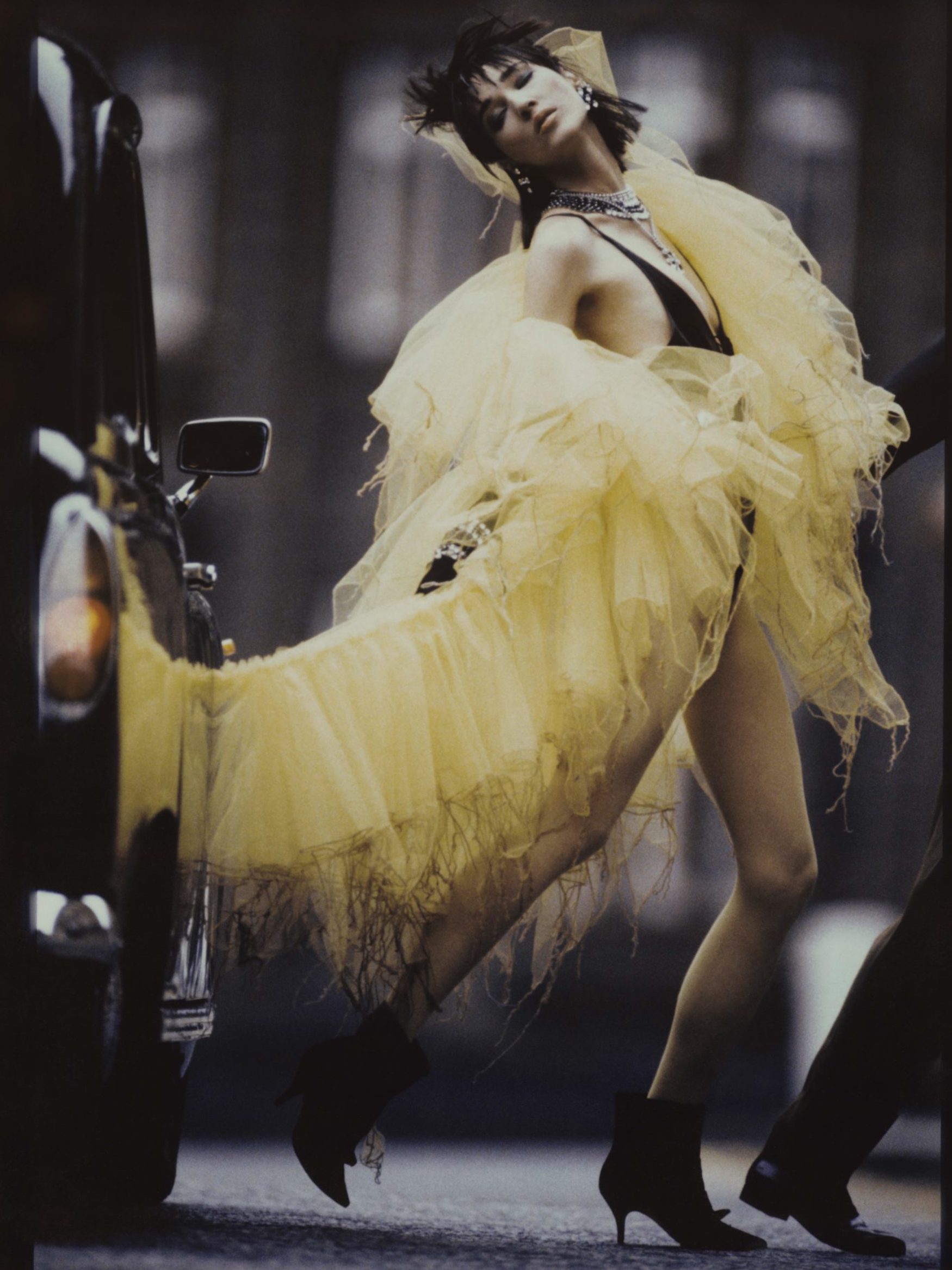

Terence Donovan, November, September 1972 © Terence Donovan Archive

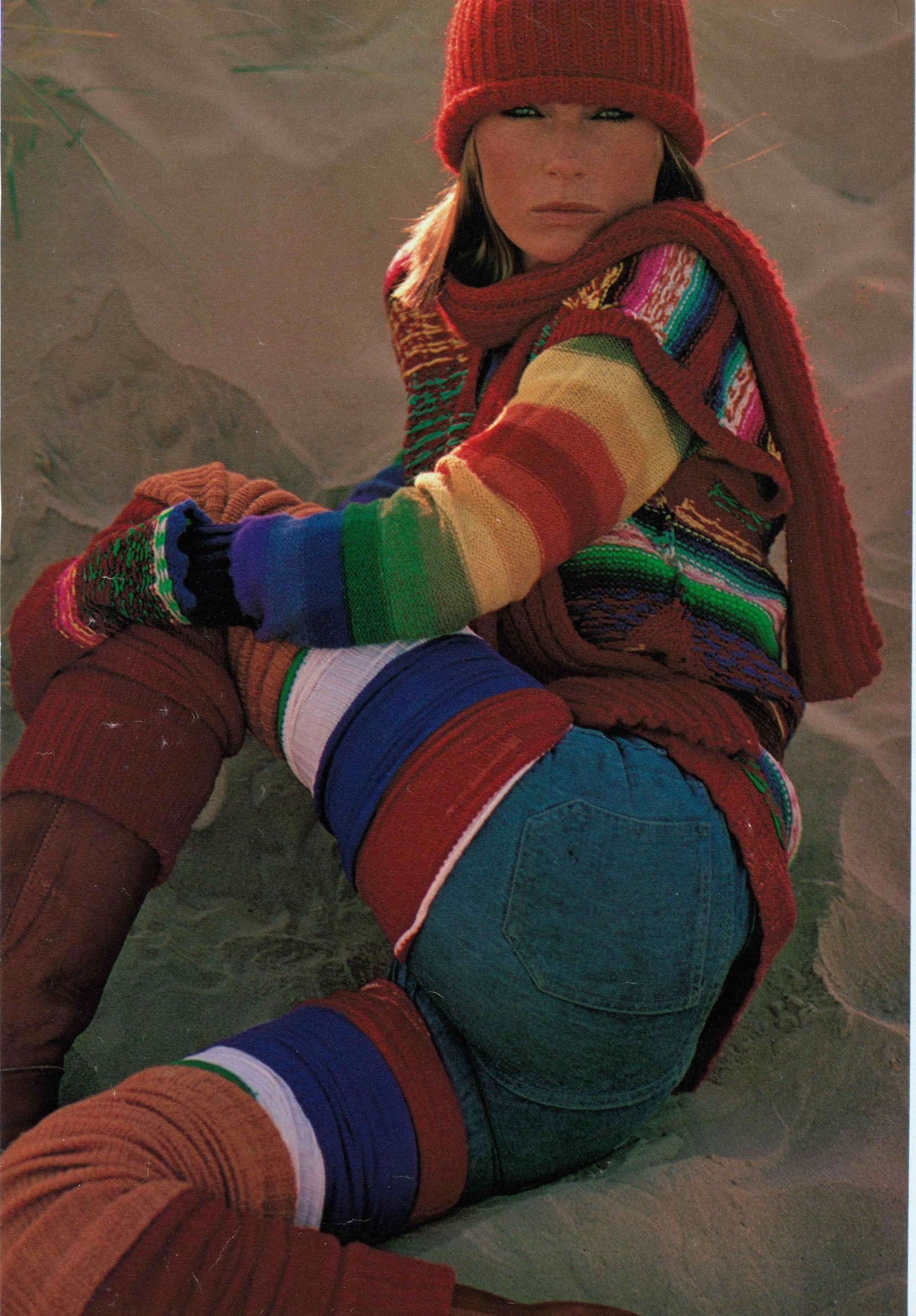

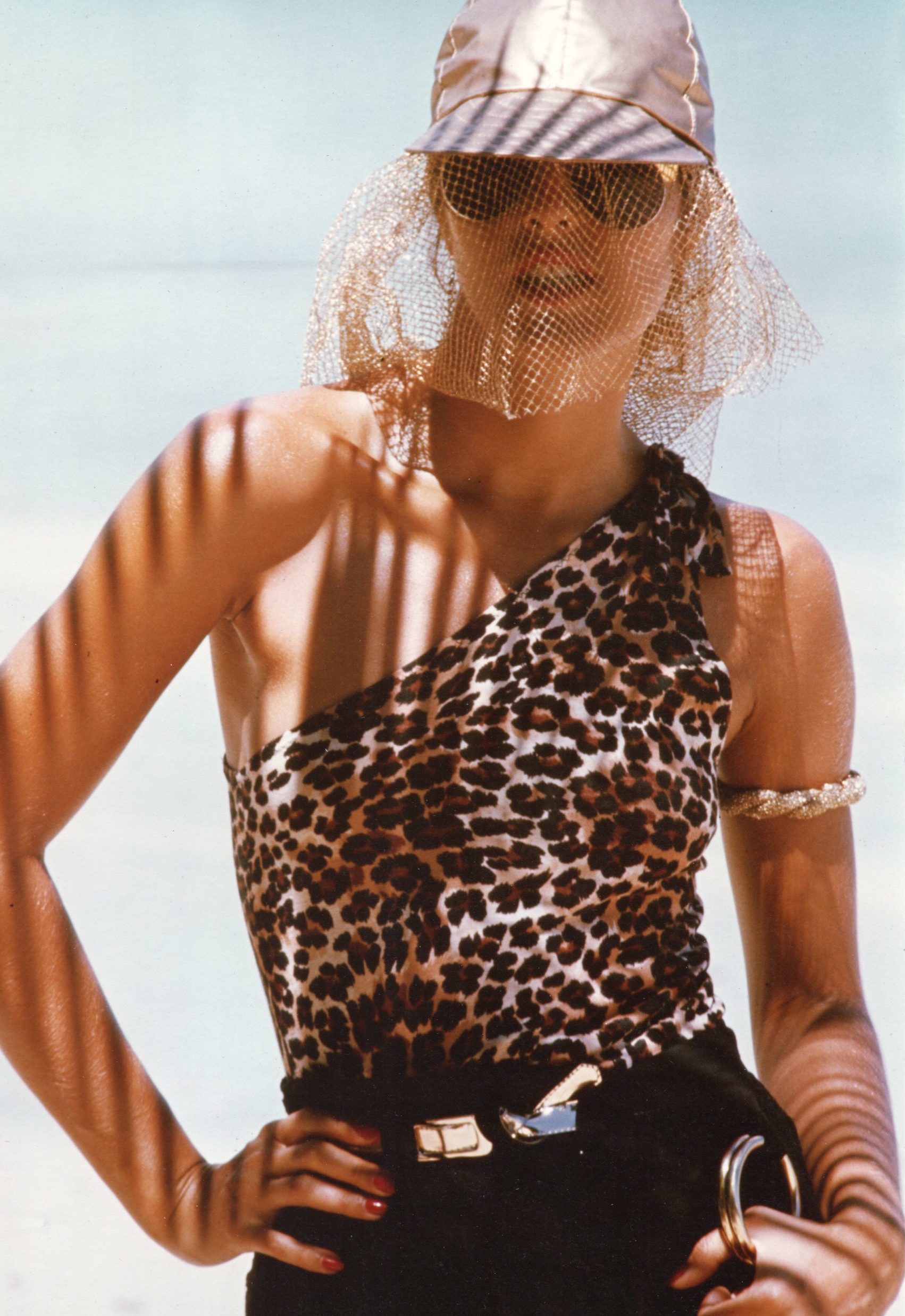

[L] Eddy Kohli, Tatler, June 1984 © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd, [R] Harri Peccinotti, Vogue, July 1976 © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd

Baker began her career at a time when a stylist’s contribution was not necessarily even credited in the creation of an image, but thanks to her daring imagination and courage to do things differently, she ended up working at the side of designers like Vivienne Westwood and Katherine Hamnett and creating some of the best-known and deliberately provocative advertising campaigns of the 1980s with Oliviero Toscani for Benetton. Tellingly, perhaps, her story is relatively unknown. “Fashion exists in the fleeting moment and is always looking to the future, yet it is tremendously important to acknowledge those who have gone before – the groundbreaking game-changers, who have paved the way by challenging convention and kicking over the traces,” says Webb. “I’m especially committed to telling stories of the often-forgotten, unsung hero or outsider… Caroline deserved a book that fittingly documented her inspirational imagery and outlook.”

She used clothes as a medium to present bigger ideas that questioned gender equality, race and social issues, consumption and sustainability, which continue to be part of current conversations. The fashion pages she constructed were as much political protest as pretty pictures.

Iain R. Webb

When Baker arrived in 1950s England from a childhood spent on an Argentinian farm, she found London on the verge of a youth-quake and after joining the revolutionary women’s magazine Nova – first as assistant to fashion editor Molly Parkin, before swiftly stepping into her boss’s shoes – she was uniquely placed to express a rebellious new mood from the streets in the magazine’s pages, shooting with the likes of Helmut Newton and Hans Feurer to create fiercely modern imagery that flew in the face of fashion publishing’s traditional elegance and elevation of luxury.

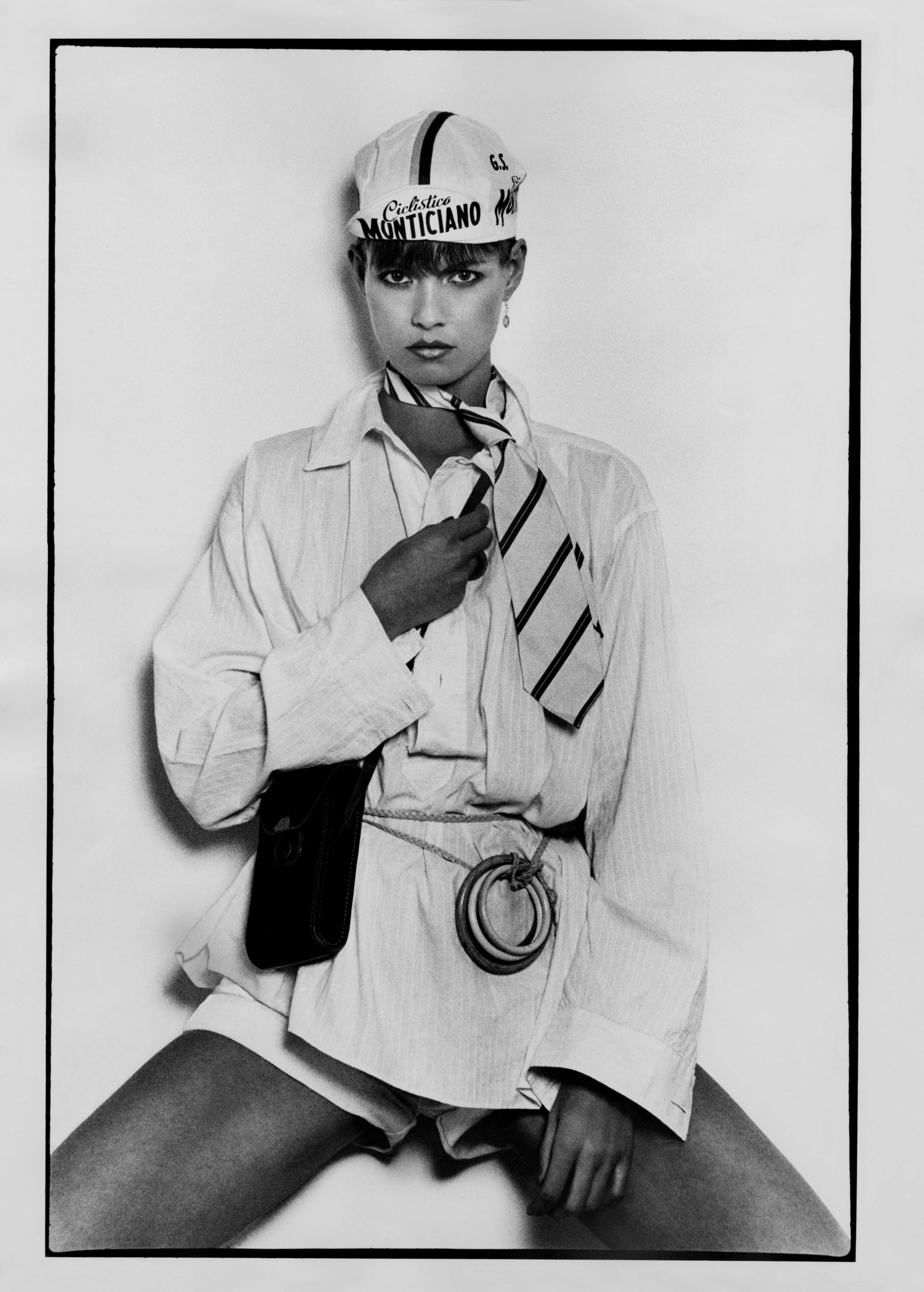

[L] Hans Feurer, Nova, November 1974 © Hans Feurer, [R] Sam Brown – i-D, November 1985 © Sam Brown

“I started to explore alternative sources of fashion,” explains Baker. “In the ’60s we were very much involved with the anti-Vietnam protest movements and everybody was wearing surplus, which I loved because I thought it was super practical – all those pockets. I thought women’s clothing was so irritating… I hated having to dress up as a doll and run around in heels and stuff.

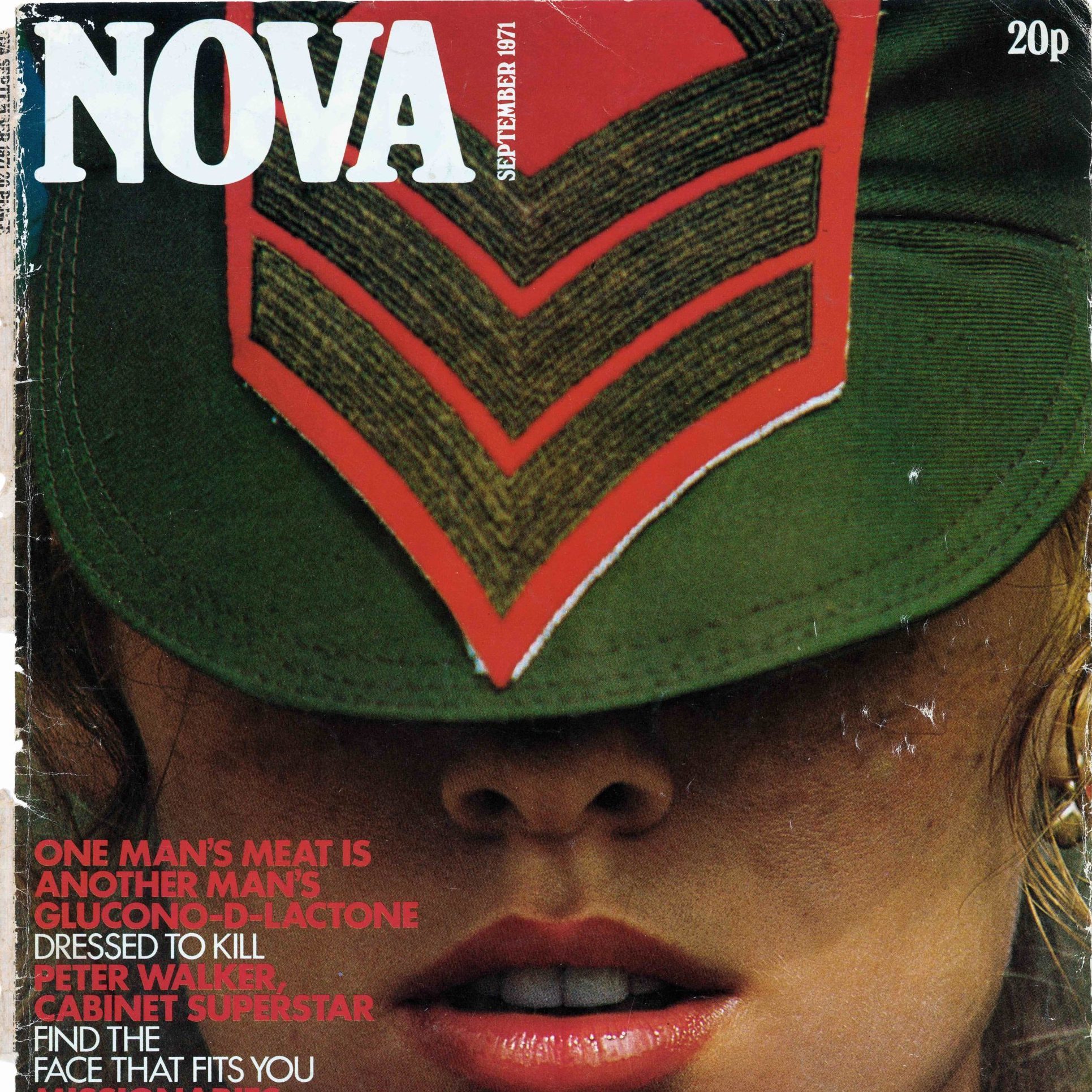

In fact, one of Baker and Newton’s most famous Nova covers depicts a model looking sultry and fabulous in a simple army surplus cap.

[L] Hans Feurer – Nova, September 1971 © Has Feurer, [R] Hans Feurer – Vogue, 15 October 1976 © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd

“Caroline’s approach was pragmatic and practical, offering her readers clothes to wear,” says Webb. “Yet at the same time… she used clothes as a medium to present bigger ideas that questioned gender equality, race and social issues, consumption and sustainability, which continue to be part of current conversations. The fashion pages she constructed were as much political protest as pretty pictures. That combination was their strength.”

As well as surplus, second-hand clothing was another important source for Baker, particularly second-hand menswear, although it was almost taboo at the time. “Moss Bros had a wonderful secondhand department,” Baker recalls, “where guys would go if they were going to a wedding.” Baker was famous for taking scissors to her finds on shoots, or maybe making a pair of menswear pants fit with by “tying a gold belt around them to make a paper-bag waist”(she loved cinching and belting garments to alter their shapes). It was this inspired and unprecious approach that she stirred into the creative melting pot when working with photographers like Sarah Moon. In fact, this is how they collaborated to create their legendary and much-referenced ‘Charlie Chaplin’ shoot in Nova in 1974.

She was the original godmother of upcycling. Says Webb: “At Nova, she cut the toes off football socks to turn them into leg warmers. Later in Cosmo, she’d advocate stitching (or pinning) some broderie anglaise ribbon onto a vest to mimic Vivienne Westwood’s pricey pirate look…

“From the get-go, Caroline relished second-hand clothes and was consistently telling her readers that they didn’t need to buy new things. She enjoyed constructing her own fashions. In this, she was as much a designer as a stylist.”

Sarah Moon, Nova, September 1971 © Sarah Moon

I was fascinated by a nugget in the book revealing that Baker had styled a fashion story using clothing entirely sourced from Oxfam shops for Tomorrow, a magazine produced by Katherine Hamnett (1984). She explains that Hamnett wanted to make that political statement, but more generally that there was at that time a new momentum and mood in the air to embrace the glory of vintage dressing. “I really think it had a lot to do with John Galliano, when he did bias but. And then you know… the ‘It girl’ thing started. Sienna Miller and Kate Moss were wearing clothes from the 1930s.”

I’m curious to know what Baker thinks of Harris Reed and his sublime upcycled Oxfam wedding dress collection, ‘Found’. “A great tailor. Just look at that beautiful evening dress [on Emma Watson],” she says, warmly, before commenting that she has noticed that Harris is a keen user of netting in his exquisite silhouettes. This is also something she approves of: “I’ve always had suitcases of net with me on set,” she laughs.

Second-hand clothing was another important source for Baker, particularly second-hand menswear, although it was almost taboo at the time. “Moss Bros had a wonderful secondhand department,” Baker recalls, “where guys would go if they were going to a wedding.”

Iain R. Webb

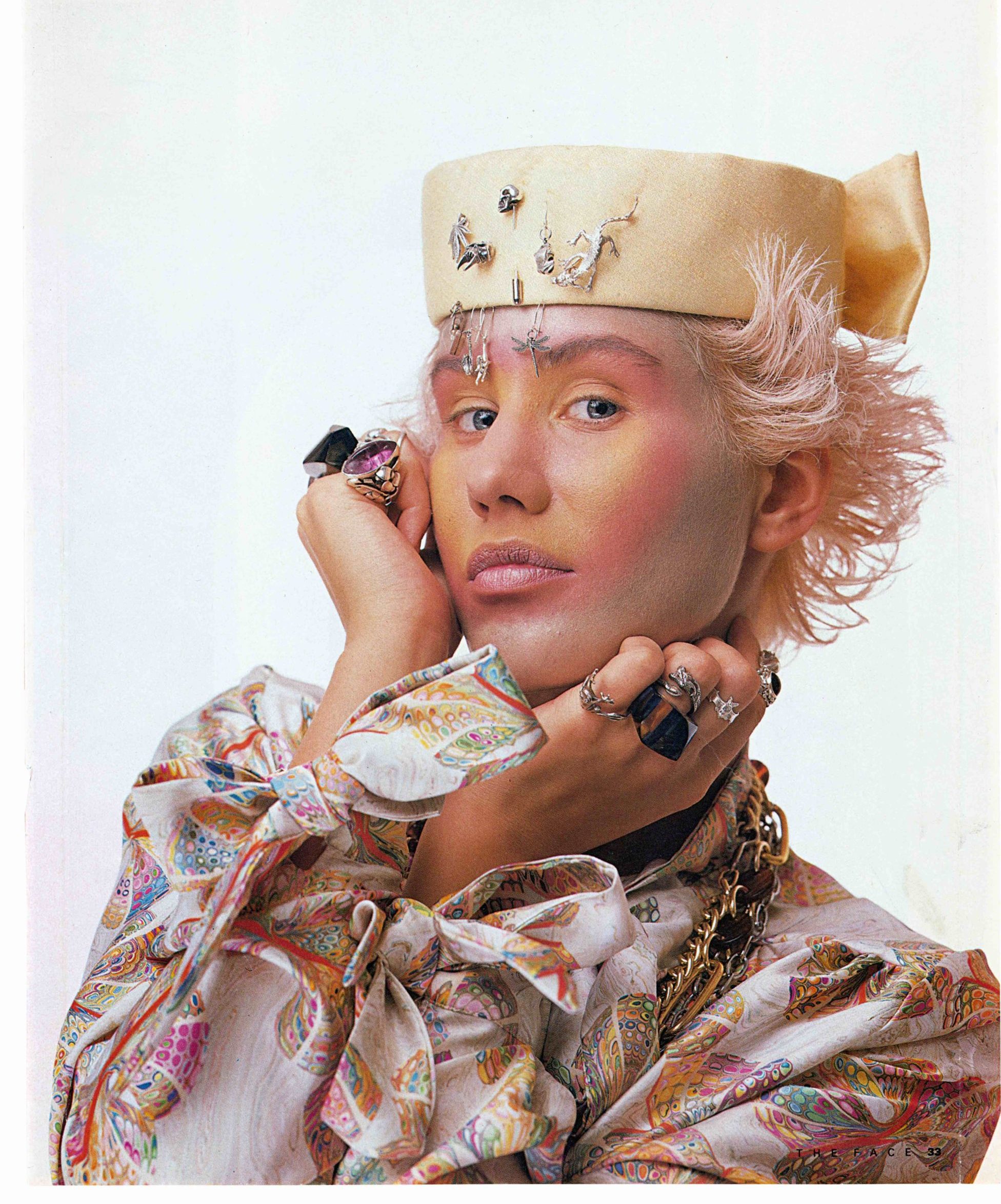

[L] Robert Erdmann, The Face, February 1985 © Robert Erdmann, [R] Ku Khanh, c.1980 © Ku Khanh

So many of the themes explored in Rebel Stylist – androgyny, anti-fashion, DIY, fashion as protest and social commentary – are utterly relevant to now. What can we learn from Baker today, I ask Webb?

“Don’t buy any more clothes! Cut up, stitch up, pin up, turn upside down and inside out clothes from the back of your wardrobe. Why follow the fashion pack, when you can make a unique fashion statement that’s really saying something!”

Rebel Stylist: Caroline Baker – The Woman Who Invented Street Fashion is available to buy now